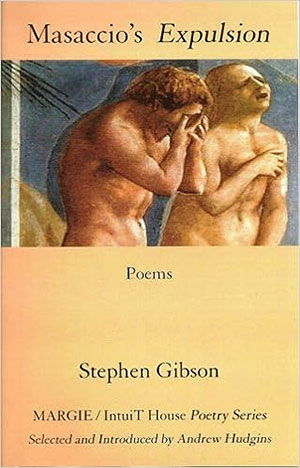

Masaccio’s Expulsion

Buy Now:

Masaccio’s Expulsion

— Poems by Stephen Gibson

winner of the MARGIE Book Prize

Masaccio's Expulsion ...is so engaging--tough, but knowing, thoughtful, and blunt, says Andrew Hudgins of Stephen Gibson's latest and the newest offering from MARGIE/IntuiT House. The book ranges from history and myth, art and life, doing so with exhilarating wit. Wit permeates the book's rage, not just at the Iraq war, but all war, exclaims Hudgins.

Because it's so engaging--tough, but knowing, thoughtful, and blunt let's assume the voice in Stephen Gibson's Masaccio's Expulsion is Stephen Gibson s. It's exhilarating for a book of poetry to implicitly ask us to suspend the useful critical cant about the speaker. The lyric poet is speaking as himself just like the rest of us! But it's natural because Gibson's voice is consistent from poem to poem, and consistently human, the voice of an imperfect but whole person struggling to live a suitable and attentive life in a world we recognize as our own. Gibson is not a put-upon confessor of existential ills, not an oversensitive poet veering toward hysteria about problems rational adults take in stride, not a word-besotted ecstatic, and not a mandarin viewing lesser mortals through the lens of a lapidary style. He's just a very smart guy who visits Europe during the beginning of the Iraq war, and who tries to reconcile the great art he knows well, with the realities of the daily news. Like us, thinks, gets angry, laughs, sorrows, loves, calls a spade a spade, changes his mind, and recognizes his limitations without setting those limitations self-exculpatingly low. Like us, except more articulate, more thoughtful, more fully engaged. In one sentence, Gibson moves quickly from overstated, if funny, annoyance (stupid, big, boorish, and a pig?) to a slightly annoying pedantry. Why is he so irritated by the man's mocking something that he himself then criticizes? But he catches himself, and we hear the charming enthusiasm. Gibson is a tourist in a church whose faith he does not share. The Bulgarian trucker is also, in a mercenary sense, a tourist accompanying American soldiers in a country where the poem suggests they do not belong. The trucker pays a wholly incommensurate price for his transgression, if that's what it is, because Al-Zarqawi, a Jordanian, is also a tourist in Iraq. Gibson has absorbed the church's sense of original sin and human depravity. He sees them played out in the news and his own instinctive anger at the boorish American. In his gut he does not believe the felix in the felix culpa, the hope of salvation through grace. But still he is in the church praying for it, for the legend that will redeem the fact. The book ranges, as this one poem does, through history and myth, art and life with wit. Wit permeates the book's rage, not just at the Iraq war, but all war. And the poet's formal dexterity is so dexterous it's almost invisible at the same time that it provides the solid and beautiful architecture of the poems. I read the book from beginning to end without stopping, twice, utterly caught up in the voice, which is the personality, which is the mind, of Stephen Gibson. Let's call him the speaker. --Andrew Hudgins